The Hidden Costs of Claude Code: Cost Optimization and Token Usage Monitoring

Anthropic hides your cost data, but here’s how to track tokens, compare subscription vs API, avoid usage limits, and save money.

In the last edition of this newsletter, I discussed how many developers were switching from Claude Code to Codex, in part because of tighter usage limits on Claude Plans. Even before the new weekly caps, the 5-hour usage limits are a common point of frustration, since you can hit a quota in the middle of your working session.

But like many others, I had no idea that Anthropic hides the token and cost information you need to optimize your way around these problems

Once you find this critical info, you can develop strategies for avoiding hitting your quota in your 5-hour window. You can also more accurately determine whether a monthly subscription is more cost-effective than using the API-key directly, in which case you pay by usage, as well as evaluate how many tokens using various MCP tools will burn. But first, you must find this info.

In this edition of AI Engineering Report, I dig into topics around understanding token usage and cost optimization on Claude Code, covering:

An invaluable OSS tool for measuring token usage in Claude Code, and pro tips on how to get the most value from it

The critical cost and token usage information that Anthropic hides in plain sight which I learned by reverse engineering how the OSS tool reverse engineers Claude Code

How to compare costs of Claude Pro and Max plans vs API key usage

Thoughts on why Anthropic makes understanding cost intentionally difficult

To work around the 5-hour reset limit, some developers on Reddit are even reporting waking up early to send Claude a quick message so that they get a fresh quota reset fairly early in their workday, meaning Anthropic has solved one of the hardest problems in software engineering - getting programmers out of bed before 8AM.

Jokes aside, I’d remind those developers that Claude Code has a non-interactive -p flag, meaning they could set up a crontab job to run a “hi Claude” early in the morning and enjoy a few extra hours of sleep.

Claude Code Usage Monitor - A Mandatory OSS Tool

It’s very interesting that Anthropic effectively hides your cost usage. If you’re on a subscription plan, the /cost command in Claude Code gives you a message like this:

> /cost

⎿ With your Claude Max subscription, no need to monitor cost — your subscription includes Claude Code usage

Given the limited quotas, Anthropic is wrong - you do need to monitor costs. Fortunately, a third party developer gave us an excellent way to do so.

Almost all of the research I did for this article comes from discovering the Claude Code Usage Monitor, developed by Maciek-roboblog on GitHub, downloading it, then having Claude Code answer my questions about how it works. This tool is amazingly useful, and I’d consider it mandatory for any Claude Code users.

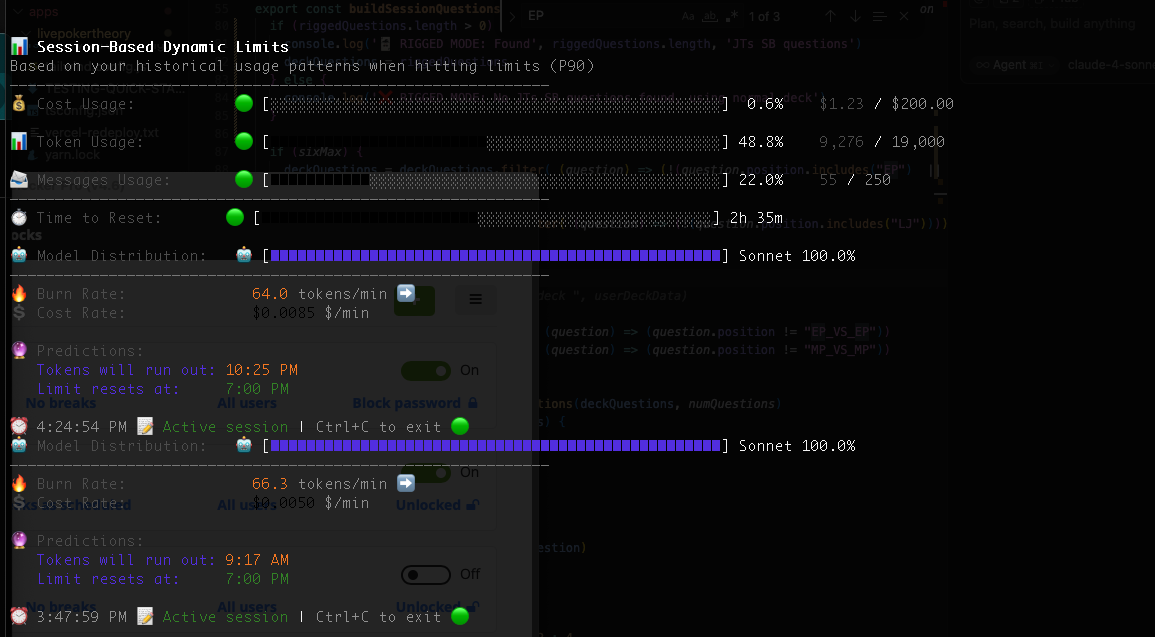

After you install it, you can run claude-monitor in a terminal window and it will show you the cost, token usage, and message limit of your current session, and the percentage you’ve moved toward your maximum quota. Keep in mind, Claude has quota on both token usage and the number of messages you send to Claude, so you should keep an eye on both. The cost is only your true cost if you’re using an API key. If you’re on a monthly subscription plan, then the cost is just what it would cost if you used the API key - which is quite helpful if you’re evaluating whether a monthly plan is cheaper than using the API key.

Just as interesting as what information this tool tells you is how it gets this information. But first, I want to provide a few more tips on using it.

Claude Code Usage Monitor - Two Pro Tips

The Claude Code Usage Monitor tool has a README that clearly explains how the product works, but it’s exhaustive enough it’s easy to miss some critical options to get the most value out of it.

My first piece of advice is that if you’re on a monthly plan, you need to tell it what your plan is with the --plan flag, like this: claude-usage --plan max20 (or pro, max5). This is important because the usage tool tells you the percentage of quota you’ve used up, but it has no way of knowing what your quota actually is without you telling it.

If you don’t provide the plan, the tool estimates your plan by looking at all your recent sessions, assuming your largest session was one that ran into a quota, and making that your max usage. This is a heuristic that might often be right, but is easily wrong if you have yet to hit your current quota. It’s best to just explicitly tell the tool with the --plan flag.

The next pro tip for this tool is that it has several different views configured with the --view flag. The default is session, but you can also look at daily and monthly. The two important ones are session and monthly .

session is important because, behind the scenes, it calculates where you’re at in your current 5-hour quota window. If you want to avoid getting stuck without Claude Code for several hours, understanding where you’re at within the current window is critical. session is the default view if you don’t provide the --view flag. (N.B. technically the default appears to be realtime which I believe is simply an alias of session).

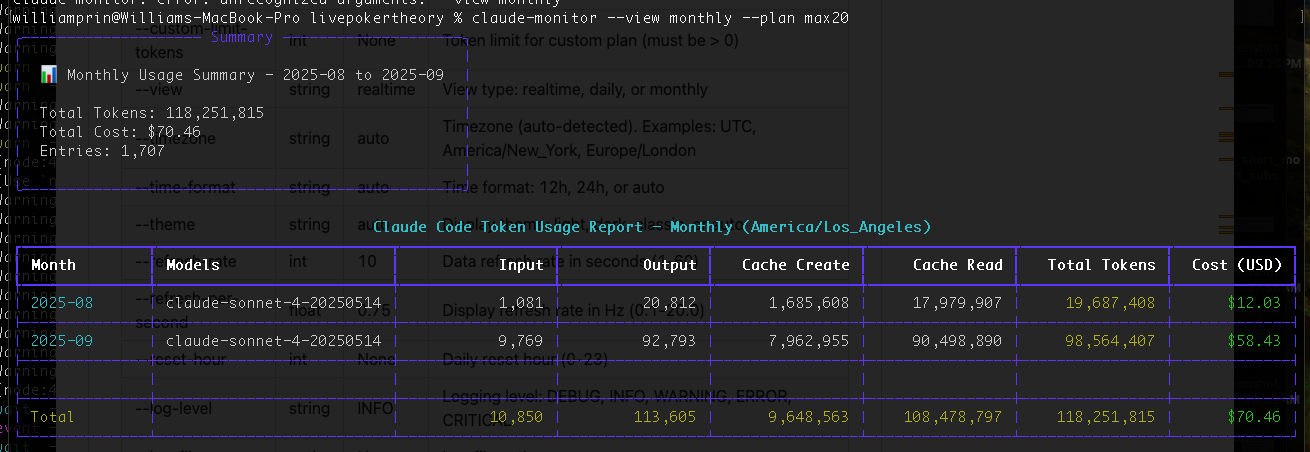

The --view monthly flag is not the default, so unless you look for it, you might not find it. As the name suggests, it shows the token usage, message usage, and API cost (or what it would be) of the current month.

The monthly view is critical if you’re evaluating between the API usage-based pricing and monthly subscription, as it’s the best way to see what your API usage-based pricing would be even if you’re on a monthly plan.

As you can see from the above screenshot, when I ran the --view monthly, I saw that I would have only spent $70.46 if I used an API key, when I’m actually paying $100/mo for Claude Max. Granted, the month is not over so I still may end up hypothetically saving money with the subscription, but the point remains that this view is the only reliable way to even make this comparison.

Unfortunately there’s no way to switch between views once you start the program, so you have to open up several instances of it or kill and restart it to switch between realtime, daily, and monthly views.

The final reason I consider this Claude Code Usage Monitor so important is that since Anthropic hides your usage statistics if you’re on the monthly plan, it’s the best way to understand token usage of various things you might do on Claude Code. For example, I’ve frequently seen people warn about tools like Playwright MCP burning many tokens, but there’s no good way of measuring how many tokens it burns without a tool like this.

Claude Code Usage Monitor - How It Works

When I first saw this usage monitor tool, I immediately wondered how it worked. Given that Anthropic doesn’t provide this info, I assumed the tool must do advanced reverse engineering of something complex like network packet captures. Out of curiosity, I downloaded the project and asked Claude Code to answer questions about it.

To my astonishment, the tool is surfacing information that Anthropic is saving locally to JSON files, and simply not revealing!

Every time you start a new Claude Code session, a JSONL file is created in ~/.claude/projects . While the ~/.claude/settings file is officially documented, this projects file remains undocumented. However, if you dig in, you’ll see that every time you create a Claude Code session, a new file is created in the projects directory.

In that file, every message that Claude Code sends to the backend API has a field showing the input_tokens and output_tokens used, which can be trivially multiplied by the current model pricing to calculate cost. This means the exact cost of each Claude Code message is sitting right on your computer in JSON format.

So all Claude Code Usage Monitor has to do is read those files to get your token usage, and multiply by $/token to get the cost. For example, to get the monthly costs, it simply reads all the JSON messages you sent this month and sums their cost. It still has a bit of nuance, for example, for the realtime view it has to determine where your 5-hour window reset occurs, but overall, the information is more hidden in plain sight than reverse engineered in a complex way.

Why Is Anthropic Hiding This Information?

It’s fascinating to me that Anthropic is putting this cost information neatly formatted on your local machine in JSONL files, then simply not showing it to you. If you are deciding between using the API key and picking a monthly plan, then how much you’d be spending with the API key is critical information. You might - like me - find that you’re paying $100/mo for a monthly plan but spending less than $100/mo on tokens, and therefore would save money with the API key.

The uncharitable interpretation would be that Anthropic doesn’t want you to save money. By telling monthly plan users, “don’t worry about usage, it’s included!”, they let a subset of users overpay for their subscription and perhaps subsidize power users. Even if you started with an API key and saw how much your usage was, you’d still need to know how many tokens you used to evaluate whether you’d be under the quota set by the monthly plans, which, like the cost, is sitting on a JSONL file on your computer but simply not surfaced to you by Claude Code.

The most charitable interpretation I could give Anthropic is that they want users to simply focus on getting value out of Claude Code and not stress over saving $20/mo by min-maxing their usage. But given how expensive AI coding can be, it’s simply inevitable that most users will care about cost optimization, and it’s hard not to suspect that Anthropic was discouraging that so that lower-usage customers could subsidize power users.

Fortunately, Claude Code Usage Monitor is here to the rescue, and if you’re a Claude Code user, it’s simply a mandatory tool. I hope this article helped you understand why it’s important and how to get the most value out of it.

Thanks for reading AI Engineering Report. Let me know your thoughts by replying to this email or leaving a comment on Substack.

I'm appreciating these articles!